Stop DrawingArchitecture beyond Representation

galleria 3

curated by Pippo Ciorra

– for young people aged between 18 and 25 (not yet turned 25);

– for groups of 15 people or more;

– La Galleria Nazionale, Museo Ebraico di Roma ticket holders;

– upon presentation of ID card or badge: Accademia Costume & Moda, Accademia Fotografica, Biblioteche di Roma, Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia, Enel (for badge holder and accompanying person), FAI Fondo Ambiente Italiano, Feltrinelli, Gruppo FS, IN/ARCH Istituto Nazionale di Architettura, Sapienza Università di Roma, LAZIOcrea, Palazzo delle Esposizioni, Amici di Palazzo Strozzi, Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, Scuola Internazionale di Comics, Teatro Olimpico, Teatro dell’Opera di Roma, Teatro di Roma, Università degli Studi di Roma Tor Vergata, Youthcard;

valid from August 1st to August 31st, upon presentation of an identity document verifying residency in the Lazio Region

valid for one year from the date of purchase

– minors under 18 years of age;

– myMAXXI cardholders;

– on your birthday presenting an identity document;

– upon presentation of EU Disability Card holders and or accompanying letter from hosting association/institution for: people with disabilities and accompanying person, people on the autistic spectrum and accompanying person, deaf people, people with cognitive disabilities and complex communication needs and their caregivers, people with serious illnesses and their caregivers, guests of first aid and anti-violence centres and accompanying operators, residents of therapeutic communities and accompanying operators;

– MiC employees;

– journalists who can prove their business activity;

– European Union tour guides and tour guides, licensed (ref. Circular n.20/2016 DG-Museums);

– 1 teacher for every 10 students;

– AMACI members;

– CIMAM International Committee for Museums and Collections of Modern Art members;

– ICOM members;

– from Tuesday to Friday (excluding holidays) European Union students and university researchers in art history and architecture, public fine arts academies (AFAM registered) students and Temple University Rome Campus students;

– IED Istituto Europeo di Design professors, NABA Nuova Accademia di Belle Arti professors, RUFA Rome University of Fine Arts professors;

– upon presentation of ID card or badge: Collezione Peggy Guggenheim a Venezia, Castello di Rivoli Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, Sotheby’s Preferred, MEP – Maison Européenne de la Photographie;

MAXXI’s Collection of Art and Architecture represents the founding element of the museum and defines its identity. Since October 2015, it has been on display with different arrangements of works.

galleria 3

curated by Pippo Ciorra

The disappearance of the traditional media of representation is proportional to the rise and evolution of the digital technologies that have gradually engulfed the profession, simplifying architects’ work, captivating their imagination and opening up new paths of research

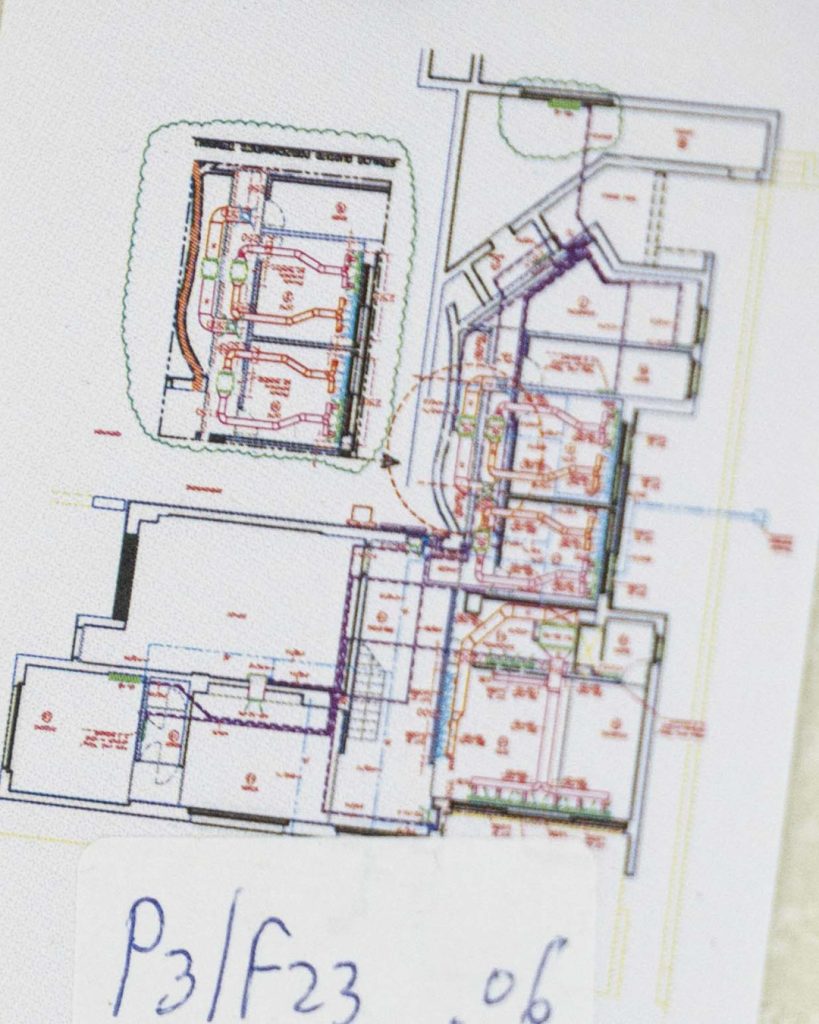

Personal computers – such as the IBM Standard PC (1981) or the Apple Macintosh (1984) – and CAD and modeling software – such as CATIA (1981), AutoCAD (1982), Microstation and MiniCAD/ArchiCAD (1985), Softimage 3D (1988) and Alias/Maya (1990) – quickly became theoretical research grounds, just as the forerunner Paperless studios at Columbia University GSAPP were in 1994.

From the seminal studies by Cedric Price and John Frazer, Christopher Alexander and Nicholas Negroponte, to the institutionalization of a new generation of digital architects with the 2003 exhibition Architectures non Standard at the Centre Pompidou, the discussion on parametric, generative, algorithmic, hyper-modern architecture has occupied two decades of the architectural debate, drastically influencing the methods of representation of the project.

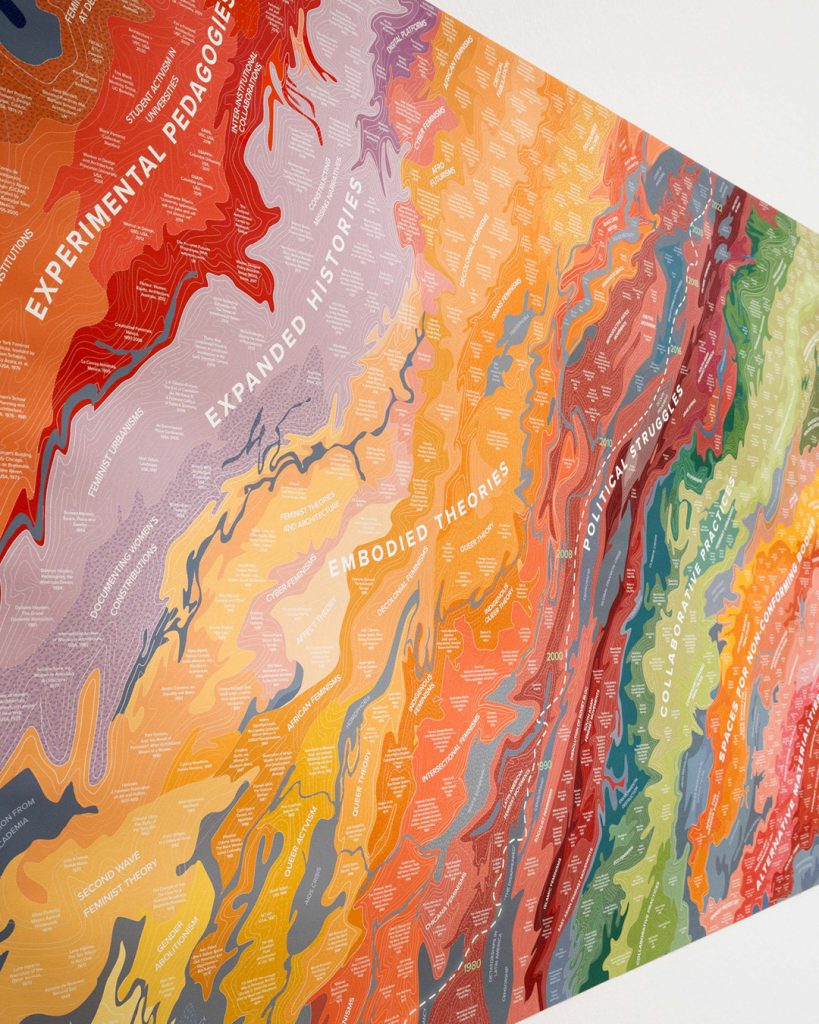

Another form of resistance to the traditional role of drawing is the one upheld by those who argue that the architects’ main task is today the civil and political one, in face of the great global issues of our time: ecology, resource management, inclusion, racial and gender equality, post-humanism and decolonisation. This choice materializes in two main operational attitudes, both represented in this exhibition.

Individual “authors”, in some way acting as flag bearers, transform the rejection of the traditional practice of architecture into an eminently theoretical action, which generally results in editorial or institutional projects.

Teams of architects, or more precisely “collectives”, on the other hand adopt a practical, hands-on approach, merging the concept of “radical” collective design, widespread in the 1960s, with the political (“forensic”) use of architectural research tools and with the direct and politically performative involvement of communities in the creation of “events” in the social context.

The constant broadening of the range of means of representation – but also of conception, speculation, interpretation – of the architectural project has expanded the possible definitions of architecture and the results that different and innovative research and approaches may produce.

“Architecture and ‘architects’ encompass very vast fields. Everyone is an architect. Everything is architecture” wrote Hans Hollein in his seminal text of 1967, almost anticipating the proliferation of artistic-architectural practices brought about by the current indeterminacy/openness of the discipline, which is well represented in this section: from collages – which Hollein himself used to create visual suggestions – to textile representations, from VR or illustrated stories to bodily experiences in space.

Architecture may arise from three-dimensional manipulations of a spatial idea, to test an architectural or structural intuition. Or it can manifest itself in an objet trouvé on which one operates through “extraction, disorientation and alteration”, questioning the very concept of architecture.

Despite the progressive push towards digitization, simulation and generative AI, there are many architects who choose to obstinately defend the traditional, technical and expressive role of drawing. This does not necessarily imply a return to drafting machines and set squares, but rather an unequivocal affirmation – applied in various ways – in favour of the historical Albertian conception, which recognises in drawing the ideological, disciplinary and artistic value of the project.

The revival of this analogous and analog instrument – be it conservative or progressive, nostalgic or symptom of a new spirit – may be considered anachronistic. However, it is difficult to ascertain if this trend arose in opposition to the predominance of digital interfaces or if, more matter-of-factly, it may also be connected to the increasingly extreme specialization that software parametric models require.

Together with society, architecture and the tools used to create and communicate it evolve. This exhibition explores these transformations through the evolution of its primary medium: drawing.

The exhibition offers a compelling exploration of the ongoing transformations within the world of architecture and the tools used to create, represent and communicate it. In the beginning, there was the drawing: an original act capable of synthesising the relationship between space, function and structure in a single gesture, an indispensable tool for any spatial thought. Then, from the final decades of the last century, we witnessed the rise of digital techniques, practices borrowed from art, exercises in political activism and hands-on participatory forms that shape the spaces we inhabit, giving less importance to “beautiful drawings”.

Works by significant figures—some drawn from the MAXXI Collection—accompany visitors on a journey through the 20th and 21st centuries. They illustrate how the ability to represent and define space, once the exclusive domain of drawing, has now expanded to include a world of digital simulations, collages, videos, performances, textiles, and more. These new representational forms can profoundly reshape the future of architecture and spatial disciplines.

Drawing is dissolving into countless different forms, presented in the various sections of the exhibition. Digital culture tends to replace it with the input of data and algorithms at the very outset of the design process. Installation, film, performance, and other creative practices are substituted for it in the work of those who aim to defend the artistic nature of architectural design. Direct engagement with lived spaces and close collaboration with communities are the preferred tools of those who believe in architecture’s political value. Finally, the exhibition touches on cases where drawing is interpreted as a choice and a form of resistance. Among the featured authors are those who seek to preserve its role in reaffirming disciplinary identity, those who oppose or aim to bend digital tools to an analogue aesthetic, and those who reject the reduction of architecture to the broad field of art, which is often – rightly or wrongly – seen as too detached from the actual structure of the world.

Six original drawing tables designed by Carlo Scarpa in the early 1970s for IUAV students, kindly loaned by the IUAV University of Venice, are used in the exhibition as display support.

header: November Wong, “The Drawing Machine”. Courtesy the artist.

exhibition's sectios

digital

activist

artistic

back to drawing